Home> Arts and Traditions

Stone dogs of Leizhou Peninsula

|

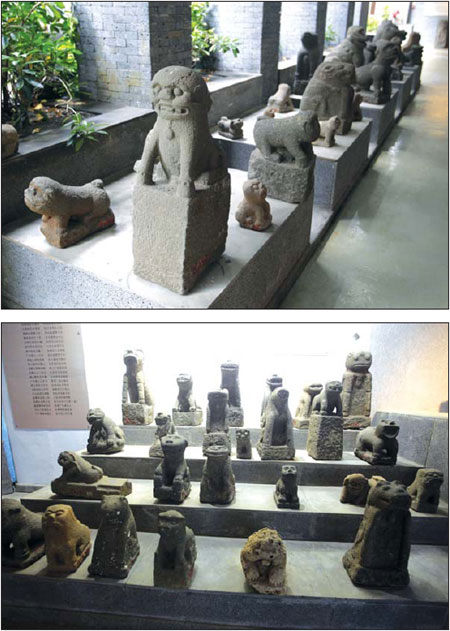

The Leizhou Museum has collected about 1,000 stone dogs that illustrate millennia-long veneration of man's best friend. |

They may not bark, but they do whisper a storied history, writes Raymond Zhou.

Wherever you travel in China, at least in Han-dominated areas, you'll encounter a stone lion as the traditional mascot guarding the entrance. But in the Leizhou Peninsula of Guangdong province, you'll more likely run into - or be daunted by - a stone statue of man's best friend.

Stone dogs are not a variation on the stone lion, but have their own unique history. They date back to a different era, with the earliest as far back as the Spring and Autumn Period (770BC-476BC).

Yet unless the statue is clearly dated, there is no scientific methodology to identify its exact age. Most figures are guesstimates based on existing knowledge about the styles of each period. Other dates were deduced from the known history of the villages where they were located or objects excavated at the same spot.

Most of the dogs were sculpted from basalt, but occasionally other materials were used, even one carved from coral. Virtually every village on the peninsula has stone dogs. More than 10,000 have been discovered.

They range widely in both size and weight, with the biggest weighing over 500 kilograms with a height of 2.5 meters, while the smallest is only half a kilogram and 10 centimeters tall.

Aboriginal worship

Leizhou Peninsula is home to half a dozen ethnic minorities that can be traced back before the Tang Dynasty (618-907), and most deified some animal or another. The Chinese characters for the ethnicity's names used to denote that trait, but it was considered chauvinistic and changed to homonyms, such as (meaning strong) for (a variety of wild dog). Some experts argue the move was counter-productive as the ethnicities themselves were proud to identify with the animals.

Farming and hunting were the most common means of survival, and people needed animals to help them. Even though the names of the ethnicities suggest different creatures were used for totem worship, there are signs that they gradually agreed on the dog as their shared object of worship because the dog was seen by all as capable of communicating with heaven.

Still, some stone dogs look like crossbreeds with other animals like cats and frogs. Chen Rongfu, a scholar who studies comparative religion, contends in his book The Evolution of Culture that the frog might have been chosen for both its resemblance to female genitalia and its reproductive power.

Eventually, the stone dog assumed a look similar to the stone lions ubiquitous elsewhere in China. Compared with the lion, the stone dogs are usually cruder or more abstract, but exhibit a richer variety of postures, assimilating features from other animals or even humans. Some were divided into civilian and military in costume, with the former sitting solemnly and the latter swaggering upright.

Unlike the stone lion, the stone dogs did not discriminate against class. They could guard households or graves regardless of an owner's social status.

Multipurpose

The Leizhou Museum in its namesake city has collected 1,000 such statues. Another museum next to the local Sanyuan Tower landmark is also dedicated to stone dogs.

The Leizhou Museum collection includes a so-called king named because of its private parts. Folklore has it that it seemed to be attached to the ground and was impossible to move.

But when someone said "You're so well-endowed you'll become king of the stone dogs", it could be moved. And viola, onwards to the museum went His Majesty.

Like the gigantic penile erection of the king, there are many stone statues with similar - albeit more modest - characteristics that speak of the ancestral obsession with procreation. According to historians, genitalia-accented dogs were most common during the Sui (581-618), Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties, when living was hard and carrying on the family lineage was best achieved by having as many offspring as possible.

The stone sculptures were seen as living creatures, and as such, their strong sexual desire also had negative ramifications as they were regarded as prone to harassing young women who happened to walk by. To address the problem, they were whitewashed before brides got on their way to a wedding.

It is said the type most popular with parents praying for more grandchildren has a canine face and human body - plus, of course, the obvious reproductive organ.

The second function for the stone dog was as an antidote to the scorching sun. In the old times, locals often prayed for rain and the solar eclipse was interpreted as the "heavenly dog biting off the sun". Coincidentally, thunder was also an object of awe, so much so that the place Leizhou was named after it (lei means thunder).

The ritual of using the canine emblem for this purpose was said to be quite simple. A dozen boys aged 8 through 12 were hired to carry on poles a bamboo or wooden chair. After they proceeded to the field, the boys would strip themselves and smear their faces with mud. Then, they would place a stone dog onto the chair and burn incense. After that, the boys would carry the poles and wave fresh bamboo shoots, thrashing the statue and imprecating: "Lord Stone Dog, please have heaven give us rain!"

They would walk around the village until the rain poured down. If the heavens did not open up, the exhausted boys would be replaced. Because local merchants would shower them with snacks, they jumped at such a ceremony even though it meant possibly long hours under the blazing sun.

A more recent usage of the stone dog was as an object that would dispel evil spirits.

Pre-Tang Dynasty, most stone dogs were placed at temples. During the Song and Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties, they were located at rice paddies and fish ponds, or ferries and bridges. Use of stone dogs in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties expanded to storefronts and roadsides, with some even used as ballast in boats.

Man-eats-dog paradox

With that history of idolatry, it is an irony that dogs also serve as a course on the menu - as a matter of fact, an endless array of courses.

As scholars attempt to reconcile the contradiction, dog worship that started with ethnic minorities waned over the years even as the rituals were carried on. At the same time, the large influx of Han Chinese brought with them the custom of treating dogs as a source of meat. It caught on and is now more intensely embraced by people in Guangdong than many places in China.

In the old days, some locals were aware of the incongruity and would forbid dog eating from certain premises. Dog eaters could gorge on their totem animal out in the wilderness and had to clean up, including a thorough mouthwash, before they were allowed back into the village or homestead. Nowadays, people are more proud of the dogs on the plate than those that they regard more or less as decorations, or antiques at best.

Yet perhaps they have gotten even closer to the spirit of their favorite animal by literally incorporating it inside.

Print

Print Mail

Mail

5G construction supports Zhanjiang's high-quality development

5G construction supports Zhanjiang's high-quality development

Acting mayor inspects project construction in Xuwen, Leizhou

Acting mayor inspects project construction in Xuwen, Leizhou Zhanjiang island an "egret paradise"

Zhanjiang island an "egret paradise"  Dancing egrets add vitality to Xiashan

Dancing egrets add vitality to Xiashan